This post has nothing to do with art or history, but everything to do with Roma! If you happened to read my interview featured on TangoDiva.com, you'll know that when I'm in Rome I can often be seen prowling the streets in the deep of night, in search of il gelato perfetto. Giolitti, near the Pantheon, has long been my favorite gelateria, as it is for so many gelatophiles.

I've just come across a July 21st dispatch on WorldHum by Valerie Ng -- a fellow Giolitti fan -- on How to Find Good Gelato in Italy. I was delighted to learn from her article that, while ice cream as we know it has a butterfat content of as high as 30%, "gelato is typically made with milk, water or soy as a base, and it has a fat content of between 1% and 10%." Ng points out that besides being healthier than ice cream, gelato's lower fat content allows one to experience the flavor more clearly, without a blanket of saturated fat dulling the tastebuds.

It seems somehow counter-intuitive that a sweet treat that's lower in fat would actually be yummier! Ahh, but what good news for those of us who have always felt we should confine ourselves to a single scoop!

Art gives me great pleasure. Especially when I have the context that leads to fuller appreciation. My travels are geared to what art is where. In this blog I share art-related items that intrigue me. Perhaps they will intrigue you, too!

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Monday, September 18, 2006

Michelangelo's Late-Life Accomplishments

I've heard people as young as 50 lament that their productive years are behind them. Perhaps it's the times, our society's idolatry of youth. Surely, the speed of technological change contributes. Perhaps in Michelangelo's day, the wisdom and experience gained over years was valued more than it is today. But to anyone who thinks (s)he's all washed up at 50, I say, "Consider Michelangelo's productivity after age 50 ..."

After 50, he sculpted 15 statues, including the masterful Dawn, Dusk, Night and Day in the Medici Chapel in Florence.

From age 62 to 67 he painted the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel, and then frescoed The Conversion of St. Paul and the Crucifixion of St. Peter in the Pauline Chapel. He was 76 when he finished them.

He became an architect! He designed and supervised the building of The Laurentian Library in Florence, and in Rome, the 3rd story cornice and courtyard of the Farnese Palace, the Piazza del Campidoglio on the Capitoline Hill, the Porta Pia, St. Peter's Basilica and its amazing dome, and ... at age 88 ... he designed the conversion of a portion of the Baths of Diocletian into the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli!

I've heard people as young as 50 lament that their productive years are behind them. Perhaps it's the times, our society's idolatry of youth. Surely, the speed of technological change contributes. Perhaps in Michelangelo's day, the wisdom and experience gained over years was valued more than it is today. But to anyone who thinks (s)he's all washed up at 50, I say, "Consider Michelangelo's productivity after age 50 ..."

After 50, he sculpted 15 statues, including the masterful Dawn, Dusk, Night and Day in the Medici Chapel in Florence.

From age 62 to 67 he painted the Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel, and then frescoed The Conversion of St. Paul and the Crucifixion of St. Peter in the Pauline Chapel. He was 76 when he finished them.

He became an architect! He designed and supervised the building of The Laurentian Library in Florence, and in Rome, the 3rd story cornice and courtyard of the Farnese Palace, the Piazza del Campidoglio on the Capitoline Hill, the Porta Pia, St. Peter's Basilica and its amazing dome, and ... at age 88 ... he designed the conversion of a portion of the Baths of Diocletian into the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli!

Wednesday, September 13, 2006

How a Centuries-Old Fresco Is Removed From The Wall

A couple of months ago I visited the The Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park in upper Manhattan. The Cloisters is a branch of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, devoted to the art and architecture of mediaeval Europe. The construction of the neo-mediaeval building and its cloisters incorporated Romanesque and Gothic architectural fragments, dating from the eleventh through the fifteenth centuries, originating primarily in Spain and France. They were brought over from Europe in the 19thC by an American sculptor, George Grey Barnard, and assembled on this site as a museum for Barnard's collection, through the generosity of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

A stone castle with cloistered gardens, set high on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River, the setting itself was worth the trip, and the mediaeval atmosphere added to my enjoyment of the art treasures on display: sculpture, tapestries, illuminated manuscripts, goldsmiths' and silversmiths' work, stained glass and enamels and ivories, and ... .

I joined a docent-led tour, which I found disappointing. It added little to what I already knew. I guess I was hoping for something along the lines of a Jane's Smart Art Guide -- that is, more substance -- for the highly-motivated person who already has some background in the subject.

Our guide wasn't able to answer the one question I posed -- "How is a fresco removed from the wall it was originally painted on?" Not only did I think he should have known, I realized that I shouldn't have had to ask!

I've wondered this before, 'though never urgently enough to look into it. This time, however, the fresco in question had been painted on a curved wall, centuries ago, in Spain. It had been removed from that wall and transported across the ocean, to be integrated into the decoration of a chapel at The Cloisters -- still (or again?) curved! There was something about the fact that it had been removed from a curved support, rather than the usual flat wall, that pushed my curiosity over the brink, into research mode!

First, it helps to understand the fresco painting technique:

Unlike a mural, which is painted onto a dry wall surface, a fresco becomes part of the wall it's painted on -- literally part of the architecture. The fresco painter would begin by preparing the wall with a coat of coarse plaster, called “arriccio”. The Italian word “fresco” -- meaning wet or "cool” -- refers not to the paint but to the surface to which the paint is applied. The surface would be coated with a finely ground plaster, which was often mixed with marble dust to increase its smoothness. This plaster -- called “intonaco”-- would be applied in very thin layers over the arriccio, whose rough surface provided the necessary adhesion.

The paint used in these mural paintings, like all paint, is made of a colored powder or pigment suspended in a medium that makes it into a liquid, which becomes a paint film when it dries. In fresco painting, the binding medium is glue and limewater. When applied to wet plaster, the limewater causes the paint to bind with the wall itself. When dry, this sort of traditionally-applied fresco painting -- known as “buon fresco” -- becomes an actual part of the wall.

Because both the paint and plaster were quick to dry, this meant that painters had to plan to work in single sessions, on patches of fresh plaster: called “giornate,” after the Italian word meaning “day’s length.”

Art conservators have learned how to separate the intonaco layer of a fresco from the underlying arriccio. The technique had to be used, for example, to save a number of frescoes in Florence after the Arno flooded its banks in 1966 and damaged numerous important Renaissance works.

A fresco is removed from the wall by being transferred onto canvas, using what's known as the "Calicot method": invented by someone named Calicot, I presume. There are two processes used, depending on the condition of the underlying plaster:

"strappo da muro" = "pulling [of the fresco] from the wall" (strappare = to pull away) and "stacco" (staccare: to detach).

The stacco process detaches the fresco painting from the wall by removing the entire intonaco layer. A special water-soluble glue is applied to the painted surface and then two layers of cloth (calico and canvas) are applied. When the glue is dry, the cloth is peeled from the wall -- very carefully, I imagine! --pulling the painted intonaco with it. Once the fresco is off the wall, stuck to the cloth, it's taken to a laboratory where the excess plaster is scraped away and a fresh canvas is attached to the back with a permanent glue. This done, the water-soluble glue is dissolved and the cloths on the face of the fresco are removed. At this point, the fresco is ready to be mounted on a new support: the canvas stretched on a frame, like a regular painting, or glued to a solid base.

The strappo process is used when the plaster on which a fresco is painted has deteriorated badly. Strappo takes off only the color layer with very small amounts of plaster. The glue that's used in strappo is considerably stronger than that used in the stacco technique, but the procedure that follows is same. Sometimes when a fresco is removed by means of strappo, a colored imprint may still be seen on the plaster remaining on the wall, evidencing the depth to which the pigment originally penetrated the wet intonaco.

And that's how they managed to get The Cloisters' fresco off a curved wall, and back onto a curved wall!

A couple of months ago I visited the The Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park in upper Manhattan. The Cloisters is a branch of New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, devoted to the art and architecture of mediaeval Europe. The construction of the neo-mediaeval building and its cloisters incorporated Romanesque and Gothic architectural fragments, dating from the eleventh through the fifteenth centuries, originating primarily in Spain and France. They were brought over from Europe in the 19thC by an American sculptor, George Grey Barnard, and assembled on this site as a museum for Barnard's collection, through the generosity of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

A stone castle with cloistered gardens, set high on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River, the setting itself was worth the trip, and the mediaeval atmosphere added to my enjoyment of the art treasures on display: sculpture, tapestries, illuminated manuscripts, goldsmiths' and silversmiths' work, stained glass and enamels and ivories, and ... .

I joined a docent-led tour, which I found disappointing. It added little to what I already knew. I guess I was hoping for something along the lines of a Jane's Smart Art Guide -- that is, more substance -- for the highly-motivated person who already has some background in the subject.

Our guide wasn't able to answer the one question I posed -- "How is a fresco removed from the wall it was originally painted on?" Not only did I think he should have known, I realized that I shouldn't have had to ask!

I've wondered this before, 'though never urgently enough to look into it. This time, however, the fresco in question had been painted on a curved wall, centuries ago, in Spain. It had been removed from that wall and transported across the ocean, to be integrated into the decoration of a chapel at The Cloisters -- still (or again?) curved! There was something about the fact that it had been removed from a curved support, rather than the usual flat wall, that pushed my curiosity over the brink, into research mode!

First, it helps to understand the fresco painting technique:

Unlike a mural, which is painted onto a dry wall surface, a fresco becomes part of the wall it's painted on -- literally part of the architecture. The fresco painter would begin by preparing the wall with a coat of coarse plaster, called “arriccio”. The Italian word “fresco” -- meaning wet or "cool” -- refers not to the paint but to the surface to which the paint is applied. The surface would be coated with a finely ground plaster, which was often mixed with marble dust to increase its smoothness. This plaster -- called “intonaco”-- would be applied in very thin layers over the arriccio, whose rough surface provided the necessary adhesion.

The paint used in these mural paintings, like all paint, is made of a colored powder or pigment suspended in a medium that makes it into a liquid, which becomes a paint film when it dries. In fresco painting, the binding medium is glue and limewater. When applied to wet plaster, the limewater causes the paint to bind with the wall itself. When dry, this sort of traditionally-applied fresco painting -- known as “buon fresco” -- becomes an actual part of the wall.

Because both the paint and plaster were quick to dry, this meant that painters had to plan to work in single sessions, on patches of fresh plaster: called “giornate,” after the Italian word meaning “day’s length.”

Art conservators have learned how to separate the intonaco layer of a fresco from the underlying arriccio. The technique had to be used, for example, to save a number of frescoes in Florence after the Arno flooded its banks in 1966 and damaged numerous important Renaissance works.

A fresco is removed from the wall by being transferred onto canvas, using what's known as the "Calicot method": invented by someone named Calicot, I presume. There are two processes used, depending on the condition of the underlying plaster:

"strappo da muro" = "pulling [of the fresco] from the wall" (strappare = to pull away) and "stacco" (staccare: to detach).

The stacco process detaches the fresco painting from the wall by removing the entire intonaco layer. A special water-soluble glue is applied to the painted surface and then two layers of cloth (calico and canvas) are applied. When the glue is dry, the cloth is peeled from the wall -- very carefully, I imagine! --pulling the painted intonaco with it. Once the fresco is off the wall, stuck to the cloth, it's taken to a laboratory where the excess plaster is scraped away and a fresh canvas is attached to the back with a permanent glue. This done, the water-soluble glue is dissolved and the cloths on the face of the fresco are removed. At this point, the fresco is ready to be mounted on a new support: the canvas stretched on a frame, like a regular painting, or glued to a solid base.

The strappo process is used when the plaster on which a fresco is painted has deteriorated badly. Strappo takes off only the color layer with very small amounts of plaster. The glue that's used in strappo is considerably stronger than that used in the stacco technique, but the procedure that follows is same. Sometimes when a fresco is removed by means of strappo, a colored imprint may still be seen on the plaster remaining on the wall, evidencing the depth to which the pigment originally penetrated the wet intonaco.

And that's how they managed to get The Cloisters' fresco off a curved wall, and back onto a curved wall!

Monday, September 04, 2006

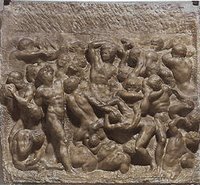

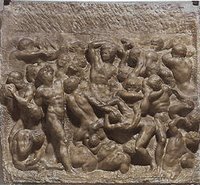

Michelangelo's Battle of the Centaurs

In June I was in Florence to test the script for the new Jane's Smart Art Guide title, Fra Angelico: San Marco Florence, which will be available in late September. We stayed at the Hotel Orto dei Medici, near the Piazza San Marco where sits the Dominican convent-turned-museum that houses Fra Angelico's wonderful fresco cycle. Our room overlooked an enclosed courtyard that apparently was part of the Medici sculpture garden where Michelangelo was taught by Bertoldo, and carved his earliest works.

I returned home with a hankering to reread Irving Stone's The Agony and The Ecstasy, which I last read -- and loved -- at age 16.

Michelangelo was about that age in 1490 - 92, when -- while residing in the Medici household and working in that garden -- he created The Battle of the Centaurs (marble, 33 1/4 x 35 1/8 inches). Both his early biographers, Condivi and Vasari, wrote that this classical subject was suggested to him by the great humanist poet and scholar, Angelo Poliziano. This is certainly a credible claim, given that Poliziano had recently translated -- from the original Greek into Italian -- Ovid's Metamorphoses, a poetic recounting of Greek legend, in which was told Nestor's tale of the battle between the centaurs and Thessalians.

"Pirithous took as bride young Hippodame;

To celebrate the day, tables were set up

And couches placed for greater luxury

Beside them in a green, well-arboured grotto.

Among the guests were centaurs, rugged creatures

(Half horse, half man, conceived in clouds they say),

Myself, and noblemen of Thessaly ...

... Oh the bride was lovely!

Then we began to say how sweet the bride was

But our intentions began to bring ill fortune to the wedding.

Eurytus, craziest of rough-hewn centaurs,

Grew hot with wine, but when he saw the bride

Was that much hotter; tables were rocked,

Turned upside down, then tossed away.

Someone had seized the bride and mounted her.

It was Eurytus, while the other centaurs

Took women as they pleased, first come, first taken,

The scene was like the looting of a city ... "

Gaiety turned to mayhem ... joy to outrage ... pleasure to plunder. That context lifted my appreciation of this work to an entirely new plane, adding a dimension of emotional involvement with the subject and an understanding of the artist's intentions that was previously impossible.

Michelangelo's Battle of the Centaurs is on display at the Casa Buonarroti in Florence. The above quote is taken from H. Gregory's 1958 translation of Ovid's Metamophoses.

In June I was in Florence to test the script for the new Jane's Smart Art Guide title, Fra Angelico: San Marco Florence, which will be available in late September. We stayed at the Hotel Orto dei Medici, near the Piazza San Marco where sits the Dominican convent-turned-museum that houses Fra Angelico's wonderful fresco cycle. Our room overlooked an enclosed courtyard that apparently was part of the Medici sculpture garden where Michelangelo was taught by Bertoldo, and carved his earliest works.

I returned home with a hankering to reread Irving Stone's The Agony and The Ecstasy, which I last read -- and loved -- at age 16.

Michelangelo was about that age in 1490 - 92, when -- while residing in the Medici household and working in that garden -- he created The Battle of the Centaurs (marble, 33 1/4 x 35 1/8 inches). Both his early biographers, Condivi and Vasari, wrote that this classical subject was suggested to him by the great humanist poet and scholar, Angelo Poliziano. This is certainly a credible claim, given that Poliziano had recently translated -- from the original Greek into Italian -- Ovid's Metamorphoses, a poetic recounting of Greek legend, in which was told Nestor's tale of the battle between the centaurs and Thessalians.

"Pirithous took as bride young Hippodame;

To celebrate the day, tables were set up

And couches placed for greater luxury

Beside them in a green, well-arboured grotto.

Among the guests were centaurs, rugged creatures

(Half horse, half man, conceived in clouds they say),

Myself, and noblemen of Thessaly ...

... Oh the bride was lovely!

Then we began to say how sweet the bride was

But our intentions began to bring ill fortune to the wedding.

Eurytus, craziest of rough-hewn centaurs,

Grew hot with wine, but when he saw the bride

Was that much hotter; tables were rocked,

Turned upside down, then tossed away.

Someone had seized the bride and mounted her.

It was Eurytus, while the other centaurs

Took women as they pleased, first come, first taken,

The scene was like the looting of a city ... "

Gaiety turned to mayhem ... joy to outrage ... pleasure to plunder. That context lifted my appreciation of this work to an entirely new plane, adding a dimension of emotional involvement with the subject and an understanding of the artist's intentions that was previously impossible.

Michelangelo's Battle of the Centaurs is on display at the Casa Buonarroti in Florence. The above quote is taken from H. Gregory's 1958 translation of Ovid's Metamophoses.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)